|

There

are a number of concerns when moving fish from one environment

to another- we are asking a lot for a fish to

adapt immediately to a

new setup in a new tank in a different place, where the tankmates,

the water quality, water

movement, filtration

type, feeding schedule, ambient light and seasonal cues may all

be different. Over many years

of breeding and working

with a number of less commonly kept species, I have found that

to best determine whether a

species will do well in

my water and setup, there appear to be three acclimation periods

to be concerned with in

any successful

introduction and acclimation to a new environment.

An awareness of these

three acclimation periods and how they play themselves out may

be the single biggest reason

some hobbyists claim they are

unable to maintain certain fish, and certainly why some claim

that a fish cannot be bred.

The initial introduction

when you first bring the fish home is the most critical, but

there are two other, longer term

adjustment periods-

mostly to your water quality, that most fish have yet to go

through once established in your aquarium.

This is added to any

other acclimations they must make to thrive in your tank, such

as getting along with tankmates, etc.

After the initial

introduction, the second acclimation takes approximately 4-5

months, and the last may not take place, for

some species, until the

3rd or 4th generation. This last acclimation becomes very

important when breeding a species that

has been difficult for you,

or when predicting possible breeding success with a species for

the long term. (Longer than just

one or two generations).

Based on experience

maintaining and breeding livebearers, where lifespan rarely

exceeds 4 years, the timing of the

acclimation periods may

vary for other longer lived fish. In other species, the process

could differ by being either

shorter or longer.

The First Acclimation:

Initially

acclimating a new fish to your aquarium:

With the initial

introduction there is more to the fish’s

acclimation than the temperature of the water, and with

a species coming from different water parameters this acclimation

process can take a couple hours. At a

minimum the process

should be done slowly if you wish for the fish to do their best.

The fish is experiencing

disruption on a health

threatening level- to just “dump” the fish into the new tank is

introducing stress at a time when

the fish can least cope

with it. To then have to deal with interactions to new, strange

tankmates on top of that can

easily be fatal to many

less hardy fish. There are two ways to best accomplish this

initial acclimation:

The “Drip Method”- Used by many aquarists, the fish after

arrival are placed into a container that will hold the fish and

the shipping water they

came in. 1/4" airline tubing is set up to siphon from a

container holding clean aquarium water or

from the aquarium they

are planned to go into. An air valve is the put on the end of

the airline just before the container

the fish are in and a

siphon is stated. The air valve is then adjusted so that a

single drop of your aquarium water then

drips into the old

shipping water no quicker than about 1 drop every 3-4 seconds.

When the amount of water in the container

then doubles- so that

half is your water, half is the shipping water, then remove

about half of it and let it continue, doing

this a couple more times.

Watch carefully throughout the process for any distress in the

fish- if they start swimming in quick

spurts or appear in

distress, jumping from the water, gasping at the surface,

resting on the bottom without energy, then stop

the dripping immediately.

Possibly add an airstone with a very light air current, and then

do not add more new water for at

least 30 minutes,

depending on how well the fish recovers. It should take at least

45 minutes to an hour before you have

the fish in 100% new

water. Then, put the fish and the water into a container (or a

bag) that will float in the tank to

acclimate the

temperature. Leave them floating for at least 10 minutes for the

water temps to equalize, before letting

the fish go into the

tank. During this time I will also feed any other inhabitants of

the tank well, so their stomachs are

full when the new fish

are introduced to the tank. This will hold down any chasing,

possible fin nipping, etc.

“Drip Method’ revised-

This is the method we use here. After using the drip system for

many years, I began to simply put

the new fish into a

container with the water they had come in (sometimes the

container may need to be angled if there was

not much water), and

would add a small amount of new water- a tablespoon or two-

about every 15-20 minutes at first. Do not

add more water if the

fish are showing any distress, and wait until they appear fine

again before adding more water. When

the water they were in

had doubled, I would start adding water more frequently and in

greater quantity. Eventually I would

start removing water, and

once they were in nearly all new water I would then float them

in the container, or a bag to even

up the temperature before

releasing them into the tank.

I also use this

opportunity to give the new fish a good meal of brine shrimp or food

they will eat while confined to the smaller

container before

releasing them into the tank. This way they too go into the new

environment with a full belly to better handle

the adjustment. Some fish

are shy when introduced to a new tank, and may choose to spend

the first couple days hiding in

the plants before coming

out to eat, feeding them well beforehand helps ease the

transition.

With all new fish, it is best

to keep them in a quarantine tank first by themselves so that

any pathogens the new fish may

be carrying cannot be spread to

the new tank.

To also help ease the

transition into their new environment, leave the light off the

first day, and provide some plants

they can hide in to feel

secure.

Acclimation #2

When adding new fish to

an aquarium, the long term adjustment to your water conditions

may be more than some fish

can tolerate long term,

particularly if the fish is fully adult or older, and had lived

its life in different water conditions.

Younger fish are able to

adjust to new water qualities more easily, and show fewer long

term effects to the adaptation to

new water. Older fish,

depending on species, and dependent on the amount of difference

between the two water qualities,

will sometimes age more

quickly and experience a shorter life span as a result of the

second adjustment period that takes

place from approximately

day 2 in their new tank, extending out to about 2-3 months.

Because you do not know how long a new fish will survive it its

new environment, the goal with any group of newly acquired

adult fish is to get them

to spawn as quickly as possible. In a sense, a gravid female is

as important as a group of older

fish- the adults, due to

the stress of the long term acclimation and change in

surroundings, may not survive more than 4

or 5 months after

arriving in your aquarium. It is always nice to have adult fish

on hand to see what any fry will grow

into, but realize that

your original fish may not be as hardy as those

that have been born and raised in your water.

The first fry born will

be far ahead in the acclimation process, more so than their

parents could have been. These are

the first born in your

water, so they need to be well taken care of as they will be the

future of that species in your

tanks.

The majority of the

species you will keep in your tank, particularly if they are

commercially produced with a long

history in the pet trade,

should adapt well. Their lifespan may be only minimally

affected, particularly if the fish

had come from water

similar to your own. However, if your intent is to get maximum

size, color and breeding success

from your new fish, any

lack of success may be tied to the fish still adapting to your

conditions.

This second acclimation

period is when the greatest mortality occurs, and when many

factors that you cannot control

will influence their survival.

The older the fish, the greater the influence their previous

life history, current overall

health and changes in

their daily routine will play. These changes include a possibly

different diet, feeding and light

schedule, possibly higher

or inconsistent ammonia and nitrate levels, pH and hardness

differences between the old

and new water, the

activity level of the tank, and new tankmates, all playing into

any prediction of how close to a full

life the fish will

continue to experience.

The most effective means

of speeding up this adjustment period, and to work toward the

best outcome is to provide

them with an environment

that provides minimal stress, allowing the fish to be

comfortable. Feed regularly with quality

food, while maintaining

good water quality. Feeding smaller amounts of quality food

often is better than feeding a large

feeding once a day.

Consider keeping only medium bright light, and provide plants

that the fish can hide into

occasionally to feel

secure. Remove any aggressive tankmates, and try to keep at

least a pair or trio to get the longest

lifespan from your new

inhabitants. Maintain good aeration and keep up on water changes

of at least 20% a week.

But there isn’t much that

you can do beyond effective husbandry, as the differences in

water qualities the fish had to

experience cannot be

changed. However, the fish will better adapt generation to

generation, and this much longer

acclimation can take 2-3

generations, and is the third adjustment some species

need to make before they

become fully accustomed to your water

qualities.

Acclimation #3

The goal of any aquarist

is to find which species will do well for them- which will grow well

with good color, and will breed

as they should. The third

acclimation is of most concern for those who wish to raise the

fish and keep that species for

many generations. Whether

your fish will do well in your tank is tied to your basic water

quality. This third acclimation

is the most important,

and is determined to have passed, often into the

third or fourth generation when they begin

to reach their full

size, live a normal lifespan, and most importantly, have large

broods of fry that grow out and do well.

Most fish can adapt to a

fairly wide range of water qualities. In any pet store, where

all of the fish are kept in the

same water, the fish are

from a variety of water conditions. Some stores may buffer their

African tanks, but generally

all of the tetras, barbs,

livebearers, catfishes and most cichlids are kept at the same pH

and hardness. Many fish will

not breed, live a full

lifespan or reach their maximum size if their water quality is

too far from where the species

originated. Anyone who

has ever worked at a pet store knows the need to remove dead

fish from the bottoms of tanks

the morning after new

shipments arrive, as a result of the adjustment to another set

of water qualities. But feeding

normally, and appearing

to thrive does not mean that the fish will breed in those

water parameters.

Once the fish has

acclimated well enough to the new conditions to appear

healthy and comfortable, acclimation

to the other variables

that differ from their previous experience continues.

This can take 2-4 months, and soon

the fish should breed. If

they do not, there may be some continued resistance to your

water quality. You may see

small broods, broods that are not

entirely healthy, or batches where a portion are stillborn.

The healthiest of those

young are then grown out and bred. Generally, after about the

3rd generation, the batches of fry

will approach normal

size, and they will begin to appear healthier and more robust.

Those fry will be the first that have

truly acclimated to your

water.

Generational time differs between species. For guppies, the

generational time used by breeders preparing for shows

is 4 months. Herbert

Axelrod mentions in his book "Fancy Swordtails' that the

generational time for the swordtails and

platies they were using

in their breeding efforts had a generational time of 8 months.

Fancy guppy breeders

encounter this multigenerational acclimation frequently when

obtaining a new line from another

breeder. Those new to

keeping expensive guppies will comment that the young fish they

bought did not grow as large

or as colorful as their

parents at the original breeders. Then their first generation

rarely looks as nice as the original

fish. They chalk it up to

the superior fishkeeping skills and foods fed at the breeder's.

However, if their water quality

was different enough from

where the fish had come from, the fish may need 2 or 3

generations before their fry become

consistent and of higher

quality. With guppies, quality is large size, vibrant color,

exaggerated finnage and vigorous

activity- all affected

when a fish is continuing to adapt to the water they are kept

in.

Guppies will breed once

they are fairly well acclimated, as will many other species that

are not difficult to breed.

But many fish cannot be

forced to adapt, however gradual the process, such that they

will one day breed. As well,

specific water qualities

may be essential to the survival of the fry- the egg membranes

may require pH and hardness

within certain limits, depending on species. Many fish simply do

not experience the natural responses to breeding cues

when the water quality is not what it should be for their

species.

In northern California where I once lived, water from the tap

was at a pH of 8.2. Angelfish and discus, for example,

that require a pH below

6.8 to breed could be bought apparently healthy from any pet

store, but they would never

breed in water so far from their

preference.

A recent example

illustrates this process. The fry of 3 wild caught pair of

Alfaro huberi were given to a friend to

develop about 5 years

ago. It took those pairs many months to drop small batches of

undersized young.. This fish

gradually increased its

numbers by just a few fish, year by year. A pair raised from the

second generation I had given

him then had a full sized batch

just this fall. It was the first time he had more than 15 of

these fish in 5 years! Those

young are full sized and

should now do well, having regular sized batches of fry of their

own in the future.

In 1998 I obtained my

first 2 pair of Zoogoneticus tequila. They did not reproduce

well, and ultimately, I needed

to obtain groups of 2

pair three more times before young were born in my water that

thrived. Today the Z. tequila

is raised by the

hundreds, and is one of the most prolific fish in the fishroom.

But it took a couple generations

for them to fully

complete their acclimation.

Currently there are three

species going through this third acclimation in the fishroom

here, and it is expected

that 2 or 3 more years

may pass before they begin to reproduce in large numbers, as

well as to reach their full

size and color. One is

Xiphophorus clemenciae. This fish has a reputation for being

difficult to maintain, with

some discussion that

certain populations are more challenging than others. The fish I

obtained were not wild

caught fish, and the

water qualities they came from were not known. The issue of the

third acclimation with this

fish is clear, as it is believed

by many aquarists that the F1s of any pair of this species will

not be fertile. This is

the third acclimation at

work- when the young of the first generation born in your water

reach breeding age, they

may still breed slowly

with smaller broods until at least another generation has

passed. As a result, many supposedly

knowledgeable aquarists

insist this fish is not fertile past its first generation, which is not true.

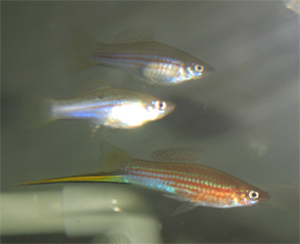

The Xiphophorus

clemenciae is a spectacular fish and the original adults were

full sized 3.5 inch fish.

(The X. clemenciae is one

of the smaller wild swordtails). However, as can be seen in the

picture below, many of the

young of the first

generation are undersized. They are healthy and robust- they are

fed 3-4xs per day with daily 15%

water changes- but will

likely require another 2 generations before the majority of the

fish in any spawn are full

sized. The X. alvarezi is

an example of a full transformation. The original fish were

obtained about 8 years ago and

were about 3.5 inches,

and bred consistently, with small batches of young that were

undersized when compared to most

swordtails. Over time,

the smallest males that were early maturing or undersized, fish

that could neither be sold or

used as breeders were

removed, and no other manipulation of the line took place. Over

time the original wild line

improved through

adaptation and optimal care. A pic of a male taken in 2012 shows

the improvement in body size and

color that has taken

place.

One fish kept here will not breed, and this multigenerational

acclimation may be to blame. So while a few pair are

being waited on to breed

in other tanks, young fry obtained from another fishkeeper are

being grown out so they may

spawn when they mature,

after having been raised in this water. Depending on how badly

you might wish to breed a

particular fish, this

process to get a spawn may take a number of months or years to

accomplish.

|

|